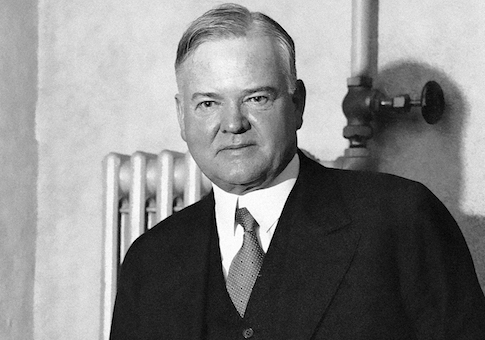

miamijaialai.org – Herbert Hoover, the 31st President of the United States, is often remembered as the leader who presided over the Great Depression, one of the most devastating economic crises in U.S. history. However, this characterization overlooks Hoover’s early efforts to prevent the economic collapse, which began shortly after his election in 1928. Hoover, who came to the White House with a reputation as an accomplished engineer and humanitarian, worked tirelessly in the years before and during the early days of the Depression to avert a financial catastrophe. While ultimately unsuccessful in preventing the severity of the Depression, Hoover’s presidency was defined by a series of bold actions and innovative proposals aimed at maintaining stability in the American economy and alleviating the suffering of ordinary Americans.

This article explores Herbert Hoover’s efforts to avert the Great Depression, his policies and approaches to economic recovery, and the challenges he faced in trying to protect the U.S. economy during a period of unprecedented turmoil. Hoover’s presidency, while marked by failure in the long run, demonstrates his vision, commitment, and the complexity of leadership during one of the most difficult periods in American history.

The Man Before the Presidency: Hoover’s Background and Early Success

Before Herbert Hoover became President, he had already earned an impressive reputation both as an engineer and a humanitarian. Born in West Branch, Iowa, in 1874, Hoover rose from humble beginnings to attend Stanford University, where he studied geology and mining engineering. After graduating in 1895, he quickly established himself as a successful mining engineer, working in Australia, China, and other parts of the world. His work not only earned him considerable wealth but also international recognition. He later transitioned into business and became a respected corporate executive.

However, it was Hoover’s work as a humanitarian during and after World War I that made him a household name. As head of the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB), Hoover organized the feeding of millions of people in German-occupied Belgium and northern France, saving countless lives. This success propelled him into the public sphere and established him as a man of action who could solve problems on a large scale. Hoover’s reputation as a humanitarian, combined with his engineering mindset, led many to believe that he was well-suited for the presidency.

When Hoover ran for president in 1928 as the Republican candidate, his campaign focused on a platform of prosperity, efficiency, and government reform. Hoover promised to build on the successes of the Roaring Twenties, a period of economic growth in the U.S., and he was seen as a leader who could maintain stability and bring efficiency to the federal government. His appeal was strong, and he was elected by a wide margin.

The Early Days of Hoover’s Presidency: Aiming for Economic Prosperity

When Hoover took office in March 1929, the U.S. economy appeared to be in a strong position. The stock market was booming, industrial production was at high levels, and the nation seemed poised for continued prosperity. However, Hoover’s optimism would soon be shattered by the unforeseen crash of the stock market in October 1929, which was to become the defining event of his presidency and the beginning of the Great Depression.

Despite Hoover’s best efforts to avert the economic collapse, the sudden and severe decline in stock prices marked the beginning of a downward spiral that led to widespread unemployment, bank failures, and an overall loss of confidence in the nation’s financial institutions. Hoover, having spent much of his career as an engineer, took a methodical approach to problem-solving and believed that the Depression could be overcome through careful planning, government efficiency, and a partnership between business and government.

Hoover’s Initial Response to the Depression

Upon taking office, Hoover quickly implemented a series of measures aimed at stabilizing the economy and preventing further deterioration. His initial response was grounded in his belief in voluntary cooperation, rather than direct government intervention. Hoover believed that businesses, labor leaders, and other sectors of society could work together to weather the storm without the need for government interference.

One of Hoover’s first actions was to convene a conference of business leaders in early 1930, urging them to keep wages and employment levels stable during the economic downturn. He hoped that by maintaining employment and wages, the economic cycle of deflation and unemployment could be avoided. Hoover also encouraged private banks to support one another and extend credit to struggling businesses, reasoning that the financial system could be stabilized without government intervention.

At the same time, Hoover pushed for a public works program to provide jobs and stimulate economic activity. In 1930, Congress passed the Federal Farm Board, which aimed to stabilize agricultural prices by purchasing surplus crops and promoting the formation of cooperatives among farmers. Hoover also supported tax cuts to encourage investment and consumer spending, reasoning that lower taxes would lead to increased economic activity.

However, Hoover’s reliance on voluntary cooperation and his reluctance to engage in direct government relief left many of his policies insufficient in the face of the worsening crisis. Despite his efforts, unemployment soared, banks continued to fail, and businesses closed at alarming rates.

The Intensifying Crisis: Hoover’s Struggle to Respond

As the Depression deepened in 1931 and 1932, Hoover’s efforts to stabilize the economy became more ambitious. However, his ideas were often met with resistance from both political opponents and business leaders, and his policies failed to stem the tide of economic collapse.

The Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC)

In 1932, Hoover took a more direct step in his attempts to stabilize the economy by creating the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), a government agency designed to provide emergency loans to banks, railroads, and other critical industries. The RFC’s mission was to provide liquidity to the financial system, prevent further bank failures, and keep major industries afloat. Hoover hoped that this would restore confidence in the banking system and prevent further economic contraction.

The RFC was an ambitious attempt to address the immediate economic challenges, but it was not without criticism. Many Americans viewed the RFC as favoring big business over the struggling working class, and its focus on loans rather than direct relief led to frustration among those suffering the most. Critics argued that Hoover was not doing enough to help ordinary people, and his belief in self-reliance and minimal government intervention was increasingly out of step with the needs of a nation in crisis.

The Bonus Army and Hoover’s Public Image

One of the defining moments of Hoover’s presidency came in the summer of 1932 when thousands of World War I veterans, known as the Bonus Army, descended upon Washington, D.C., to demand early payment of a bonus they had been promised for their military service. Hoover’s decision to send the U.S. Army to forcibly remove the veterans from their makeshift camps, using tanks and troops, sparked widespread outrage. The violent eviction, which resulted in the deaths of two veterans, severely damaged Hoover’s reputation.

The Bonus Army incident marked the turning point in Hoover’s presidency. Public opinion turned sharply against him, and many saw him as out of touch with the struggles of ordinary Americans. The crisis of the Great Depression was no longer seen as something that could be solved by voluntary cooperation and limited government intervention. The American people were looking for a more active and direct response to their suffering.

The 1932 Election and Hoover’s Defeat

As the 1932 presidential election approached, Hoover’s approval ratings plummeted. The nation’s economic troubles, combined with the failures of Hoover’s policies, led to widespread dissatisfaction with his leadership. Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Democratic candidate, promised a new approach to the Depression with his New Deal platform, advocating for direct government intervention in the economy, relief programs for the unemployed, and the regulation of the banking system.

Roosevelt’s vision stood in stark contrast to Hoover’s philosophy of limited government, and in the election of 1932, Roosevelt won in a landslide, carrying 42 of the 48 states and securing 57.4% of the popular vote. Hoover’s defeat marked the end of his political career, but it did not end his work or his contributions to public life.

Hoover’s Legacy: A Visionary, but One Who Could Not Prevent the Storm

While Herbert Hoover’s presidency is often remembered for his inability to prevent or mitigate the effects of the Great Depression, his efforts should not be dismissed entirely. Hoover’s response to the economic collapse demonstrated his deep commitment to public service, his belief in self-reliance, and his desire to limit government intervention. While his policies were insufficient for the scale of the crisis, Hoover laid the groundwork for future government responses to economic crises, especially through the creation of institutions like the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC).

Hoover’s vision of recovery focused on voluntary cooperation, public-private partnerships, and limited government intervention. While these ideas were ultimately inadequate in the face of the massive economic upheaval, they reflect Hoover’s commitment to a belief in the potential for cooperation and the importance of maintaining individual responsibility during times of adversity.

In hindsight, Hoover is often criticized for failing to take more aggressive action in the face of the Depression. However, at the time, Hoover’s policies were seen as bold and forward-thinking. His reliance on market forces, rather than direct government intervention, was consistent with the principles of his era and the ethos of his Republican Party. Hoover’s failures should not overshadow the challenges he faced in trying to steer the U.S. through an unprecedented crisis.

Conclusion: The President Who Tried

Herbert Hoover is often remembered as the president who could not stop the Great Depression. However, his presidency was characterized by efforts to avert economic collapse and his belief that recovery could come through cooperation and government efficiency. Despite the failure of many of his policies, Hoover’s responses to the crisis were grounded in a sincere desire to stabilize the nation and protect the American people.

Though Hoover’s presidency ended in defeat, his post-presidential years would reveal a man committed to public service and international humanitarian efforts. As history has shown, Hoover’s legacy as a president is far more complex than the label of a failed leader. His presidency was marked by a vision of recovery that, in hindsight, may have been too optimistic. Still, Hoover’s attempts to avert the Depression deserve recognition as an important chapter in the history of American leadership during a time of profound economic hardship.